A week ago I received an email regarding the same conversation that Mike Klonsky has so eloquently written about on his blog. I am reprinting Mikes work in its entirety. I will also post the rest of the conversation below in the first comment (its a little long but definitely worth the read). Although Mike does a pretty good job of summing up the “small schools” part of the conversation, there is even more to be said about the common ground reached in regards to the common enemy of education the NCLB act.

"If these two can find common ground, why can't we have peace in the Middle East?

Veteran educators Deborah Meier and Diane Ravitch are usually at odds, philosophically and practically. But they have opened up a dialogue which has led them to common ground. Neither has any tolerance for the current standardized testing madness. The latest issue of Edweek carries their co-authored piece: "Bridging Differences," which reads like a memo of understanding between the U.S. and China.

They still are miles apart on issues of mandated curriculum, for which Meier has no use.

Unlike Deborah, Diane has long supported an explicit, prescribed curriculum, one that would consume about half the school day, on which national examinations would be based. Diane believes in the value of a common, knowledge-based curriculum, such as the Core Knowledge curriculum, that ensures that all children study history, literature, mathematics, science, art, music, and foreign language; such a curriculum, she thinks, would support rather than undermine teachers’ work. Deborah, while strongly agreeing on the need for a broad liberal arts curriculum, doubts that anyone can ensure what children will really understand and usefully make sense of, even through the best imposed curriculum, especially if it is designed by people who are far from the actual school communities and classrooms.

Unlike Deborah, Diane has long supported an explicit, prescribed curriculum, one that would consume about half the school day, on which national examinations would be based. Diane believes in the value of a common, knowledge-based curriculum, such as the Core Knowledge curriculum, that ensures that all children study history, literature, mathematics, science, art, music, and foreign language; such a curriculum, she thinks, would support rather than undermine teachers’ work. Deborah, while strongly agreeing on the need for a broad liberal arts curriculum, doubts that anyone can ensure what children will really understand and usefully make sense of, even through the best imposed curriculum, especially if it is designed by people who are far from the actual school communities and classrooms. For me, the most interesting point of agreement in this amazing dialogue, has to do with small schools. Meier has long been viewed as the godmother of small schools, the founder of the first of the modern small schools, Central Park East in New York, and a consistant voice in their defense. Ravitch has argued that we should be worried about schools getting "too small" to support her core curriculum. (See my Nov. 9, 2005 blog post: "Diane Ravitch Barking Up the Wrong Tree ").

But they both find common ground in their critical view of the current, often thoughtless, mass-replication approach to small schools.

Deborah is a pioneer of the small-schools movement. Diane, while not an opponent of that movement, has questioned whether such schools have the capacity to offer a reasonable curriculum, including advanced classes. Yet here, too, we both fear that a good idea has too often been subverted by the mass production of large numbers of small schools, without adequate planning or qualified leadership and with insufficient thought given to how they might promote class and racial integration, rather than contribute to further segregation. "

.

Most of the stuff Mike writes about is in refference to the small school movement. I highly suggest checking out his blog linked above if you have a moment.

1 comment:

Bridging Differences

A Dialogue Between Deborah Meier and Diane Ravitch

By Deborah Meier & Diane Ravitch

In the course of the last 30 years, the two of us have been at odds on

any number of issues—on our judgments about progressive education, on

the relative importance of curriculum content (what students are

taught) vs. habits of mind (how students come to know what they are

taught), and most recently in our views of the risks involved in

nationalizing aspects of education policy.

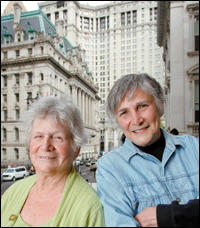

Two renowned educators with often-opposing views, Diane Ravitch, left,

and Deborah Meier, share a lighter moment outside the Tweed Courthouse

building, the headquarters for the New York City school system.

—Todd Pitt for Education Week

Meeting recently to prepare for a debate on the federal No Child Left

Behind Act, however, we found ourselves agreeing about the mess that

has been generated by local and state testing. Both of us agreed that

the public needs far better information about both inputs and

outcomes, without which the public is woefully uninformed and too

easily manipulated. As we discussed what the next policy steps should

be, Diane preferred a national response, and Deborah preferred a local

one.

As we talked further, we were surprised to discover that we shared a

similar reaction to many of the things that are happening in education

today, especially in our nation's urban school districts. Recent

trends and events seem to be confirming our mutual fears and

jeopardizing our common hopes about what schooling might accomplish

for the nation's children. We might, we agreed, be getting the worst

of both our perspectives.

Unlike Deborah, Diane has long supported an explicit, prescribed

curriculum, one that would consume about half the school day, on which

national examinations would be based. Diane believes in the value of a

common, knowledge-based curriculum, such as the Core Knowledge

curriculum, that ensures that all children study history, literature,

mathematics, science, art, music, and foreign language; such a

curriculum, she thinks, would support rather than undermine teachers'

work. Deborah, while strongly agreeing on the need for a broad liberal

arts curriculum, doubts that anyone can ensure what children will

really understand and usefully make sense of, even through the best

imposed curriculum, especially if it is designed by people who are far

from the actual school communities and classrooms.

Yet both of us are appalled by the relentless "test prep" activities

that have displaced good instruction in far too many urban classrooms,

and that narrow the curriculum to nothing but math and reading. We are

furthermore distressed by unwarranted claims from many cities and

states about "historic gains" that are based on dumbed-down tests,

even occasionally on downright dishonest scoring by purposeful

exclusion of low-scoring students.

What unites us above all is our conviction that low-income children

who live in urban centers are getting the worst of both of our

approaches.

Deborah is a pioneer of the small-schools movement. Diane, while not

an opponent of that movement, has questioned whether such schools have

the capacity to offer a reasonable curriculum, including advanced

classes. Yet here, too, we both fear that a good idea has too often

been subverted by the mass production of large numbers of small

schools, without adequate planning or qualified leadership and with

insufficient thought given to how they might promote class and racial

integration, rather than contribute to further segregation.

We found that we were both dismayed by efforts in New York City to

micromanage what teachers in most K-8 schools do at every moment in

the day. While Deborah allies herself with many of the so-called

constructivist ideas about teaching that are now in vogue in New York,

she believes that the very idea of constructivism is mocked by the

city's too often lock-step and authoritarian approach to implementing

such ideas. In our shared view, the city's department of education has

no curriculum at all, just a mandated and highly prescribed pedagogy

in grades K-8, after which time the state Regents examinations—tests

that have been dramatically simplified in recent years—serve as an

implicit curriculum.

We concur that teachers must be free to use their best professional

judgment about how to teach, and we agree on the importance of a

strong professional culture in which teachers are encouraged to

question and re-examine pedagogical assumptions and practices. Deborah

would want teachers to continually re-examine curricular assumptions.

Diane urges the adoption of a prescribed curriculum that includes at

least the central academic disciplines and the arts. She believes that

a policy of letting a thousand flowers bloom without tending is likely

to produce hundreds of weeds and only a few rare flowers. Deborah

agrees; good gardens need tending. She would leave most of the details

to the local school community.

We both recognize that wise teachers have always found ingenious ways

to sabotage any and all demands for compliance. It is hard, if not

impossible, to run a perfect lock-step system when professionals (if

they really are professionals) expect to make decisions and exercise

discretion. Resistance to nonsense is one of the habits that citizens

need to hone in a free society. But much of the sabotage that occurs

behind classroom doors, we recognize, may disguise watering down the

curriculum or evading responsibility.

During our animated conversation, we agreed that a central, abiding

function of public education is to educate the citizens who will

preserve the essential balances of power that democracy requires, as

well as to support a sufficient level of social and economic equality,

without which democracy cannot long be sustained. We agreed that the

ends of education—its purposes, and the trade-offs that real life

requires—must be openly debated and continuously re-examined. Young

people need to see themselves as novice members of a serious,

intellectually purposeful community. We think that it would be healthy

if students listened to and participated in such discussions, and came

to understand the purposes for their schooling beyond the need to

acquire more certificates.

These central convictions, rarely discussed these days, led us to

agree also on the importance of a strong adult role—including parents,

community, principals, and teachers—in the raising of children; on the

importance of knowing young people well, if we are to influence their

futures; on the risk of placing young people in anonymous,

peer-dominated environments in which the adults in authority are

disrespected and hold little genuine power to shape or make decisions;

on the lack of time for faculty members to become professional experts

in either the content or pedagogy of their craft; and on the important

role played not only in schools, but also in American life, by unions,

which not only represent the common interests of their members, but

also serve as a necessary counterbalance to the power of huge blocs of

money.

What unites us above all is our conviction that low-income children

who live in urban centers are getting the worst of both of our

approaches. New York City is a prominent example. No central, abiding

definition of what constitutes a well-educated person unites or

rationalizes the mandates that flow from central headquarters. The

substance of education—history, science, social science, literature,

art, music—never sufficiently honored in most of our schools, is being

sacrificed to narrowly focused demands to produce higher test scores

in reading and math.

Principals and teachers, regardless of their experience, are ordered

to comply with mandates about how to teach—down to the minute in many

elementary schools—undermining not only their professionalism, but

often their common sense. A particular style of teaching has been

elevated to a cult, for fear that teachers might err if given more

leeway to make decisions and do what they think best. Fear is

widespread among teachers, principals, and kids alike, none of whom

have any strong countervailing institutions to count on for support.

The ends of education—its purposes, and the trade-offs that real life

requires—must be openly debated and continuously re-examined. Young

people need to see themselves as novice members of a serious,

intellectually purposeful community.

Almost all the usual intervening mediators—parent organizations,

unions, and local community organizations—have either been co-opted,

purchased, or weakened, or find themselves under siege if they

question the dominant model of corporate-style "reform." All the

city's major universities, foundations, and business elites are joined

together as cheerleaders, if not actual participants, offering no

support or encouragement to watchdogs and dissidents. This allows

these elites the opportunity to carry out their experiments on a

grand, and they hope uninterrupted, "apolitical" scale, where

everything can, at last, be aligned, in each and every school, from

prekindergarten to grade 12, under the watchful eye of a single

leader. If they can remain in power long enough, it is assumed

(although what actually is assumed is not easy to find out) that they

can create a new paradigm that no future change in leadership can undo.

Along with the power to impose practice, we are concerned about the

inability to discuss—or even discern—the nature of the long-term

picture that our corporate leaders have in mind for the city's public

schools. Is the "autonomy zone," which New York City has established

for several score of mostly small schools, the wave of an undefined

future, or is it just a place to park some difficult dissidents to

quiet them while other schools are brought into compliance? New York's

latest plan of "devolution" is once again the work of a small cadre of

corporate-management experts, formulated without public input, not

even from those most affected by it. In Chicago, one of many cities

embarked on similar programs, autonomy is offered to private

entrepreneurs who are invited to "remake" public schooling in

union-free zones. It is hard to know what these experiments portend,

whether they will lead to greater freedom for certain schools, or for

most schools, or whether they are actually a first step towards

dismantling the governance of public education.

New York City also has launched more than a hundred new schools of

choice, especially at the secondary level, including dozens of schools

open only to selected, high-achieving students. Selectivity is hardly

a new practice in New York. Within-school tracking, after all, often

served similar purposes. But the latest reforms contain disturbing and

unacknowledged implications. Many students are assigned to "schools of

choice" that the students themselves have not chosen. When big schools

are closed down, thousands of students are relocated to the remaining

large schools, causing extreme overcrowding since there are not enough

seats for all of them in the new small schools. In some cases, the new

schools have excluded students who require special education services

or have limited English proficiency. And all of this is happening in

the name of equity and "closing the achievement gap" and other

unimpeachable rhetoric.

As we talked, we found ourselves deeply frustrated, even angry, as we

realized that the so-called reforms of the day are too often a

perverse distortion—one might say an "evil twin"—of the different

ideas that each of us has advocated.

We acknowledged that our disagreements are both deep and important.

Diane believes that national standards and a national curriculum would

give everyone access to what only the elites now learn. She argues

that the curriculum most schools teach is already a national

curriculum, but is characterized by mediocrity and superficiality,

based on boring textbooks, and assessed by tests that are as banal as

the curriculum. Deborah agrees about the latter, but believes

individual schools and families must have more, not less, power to

decide not only how to teach, but also what is to be taught, and that

schools must be able to respond to local circumstances, the passions

of students and teachers, and the experimentation required to meet the

astounding demand that "all children shall achieve what only a few

once did."

Both of us also acknowledged that our choices involve risks. A

national curriculum might be unwieldy and superficial ("a mile wide

and an inch deep"—ironically, the charge directed at our current

incoherent and fragmented curriculum) as well as politically

compromised, while a local one might reflect the low expectations of

the local community as well as local foolishness and local biases

(some schools, for example, might teach intelligent design). We agreed

that the measurement of "results"—what constitutes intellectual

achievement—has been badly distorted by current local and state tests,

which undermine high-quality tasks and make a mockery of critical

thinking. But we disagreed on whether a national test similar to the

National Assessment of Educational Progress would be better, or

whether some newly fashioned, open-ended, high-quality test was even

feasible, much less desirable.

Deborah Meier, left, and Diane Ravitch urge more discussion of

conflicting ideas about schooling, making educators models of

democratic engagement.

—Todd Pitt for Education Week

Deborah, more than Diane, worries about the impact on teaching, and on

relationships among teachers and between teachers and their students,

when the authority to examine ends, not just means, is outside

teachers' influence, and how easily the one could end up dictating the

other. She is even more concerned that being able to dictate what is

taught could infringe on intellectual freedom; she prefers a free

marketplace of diverse ideas about what is important and why. She

argues that the imposition of one official version of history, for

example, would override our different views. Why, she asks, do we

assume that "local politics" is necessarily more suspect—more corrupt

or petty—than national politics? This itself, she suggests, is a risky

proposition for a society determined to nourish the democratic idea.

Diane is more optimistic than Deborah about the possibility of

crafting a lean curriculum that avoids any prescriptions about how to

teach, and developing assessments to go with them. She points out that

many other countries (such as Britain, France, and Japan) have done

this without compromising intellectual freedom. In her view,

intellectual freedom may be even more endangered by the continual

dumbing-down of curriculum and tests that is the consequence of

allowing every district and state to define science, mathematics, and

other subjects in its own way, without regard to existing

international standards. If one wants to find an "official history"

that overrides our different views, she argues, just line up the

leading history textbooks, and there it is.

Deborah worries that federalizing education policy would open up new

opportunities for elites to impose their agendas, as is already

happening in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other locations. If

textbooks already do so, she argues for less, not more, reliance on

them. She is prepared to accept the risks of local, parochial agendas

rather than risk the centralized power over ideas. She is concerned

that federal control of education would lead to a further drying up,

in community after community, of any sense of local voice, and the

growth of a sense of powerlessness and alienation from public life.

This alienation, she fears, is a more potent danger to democracy than

any real or imagined loss of academic purity. She fears the arrival of

federally approved texts and programs, all in the name of improving

scores on nationally normed tests. She argues that federal control

would lead to the same meddling and dumbing-down on a national scale

that we now see at the local and state levels, and would increase a

trend toward the privatization, as opposed to the localization, of

school choice. Teachers cannot pass on an imposed curriculum that does

not connect to their own or their students' understanding, Deborah

argues, and trying to do so distorts the very ends that such a

curriculum seeks: thoughtful habits of mind.

Diane points out that the federal government has traditionally been

the guarantor of equity in school affairs, because it is not ensnared

in local politics. Any federal standards would aim to lift the

performance of all American students, and to equalize life chances

between haves and have-nots. If curriculum and standards were

federally determined, rather than determined by the states, she

argues, there would be no reason to require that texts or programs

receive federal approval. In her view, the current system of low

standards or no standards affirms a reign of mediocrity and

legitimates the inequitable distribution of knowledge. However,

national standards need not be federal standards, and they need not be

compulsory. They might be developed by private groups, such as the

College Board, and made available to schools that accept these goals.

Even if national tests were administered by the U.S. Department of

Education, as the NAEP tests are, Diane believes that experience has

shown such tests to be less subject to the politics of dumbing-down

than are local and state tests. At the very least, she argues,

everyone would get accurate—or at least comparable—information about

student and school performance. That, in itself, would be a huge

improvement over the current situation, in which many states have

lowered their standards to declare nonexistent gains in student

learning.

The so-called reforms of the day are too often a perverse

distortion—one might say an "evil twin"—of the different ideas that

each of us has advocated.

Deborah considers NAEP to be flawed in ways not dissimilar to most

standardized tests, and she regards its cut scores and norms as

equally politically determined and, at present, absurdly high. She

notes that the view of the federal government as the guarantor of

equity was the product of a particular time and place in our history,

and sees no reason to assume that the federal government is likely to

be better intentioned about education policy now, or in the future,

than local communities are. She believes that certain conservatives

favor national standards and testing because they are in power. Diane

points out, however, that most conservatives are adamantly opposed to

any national standards, while President Clinton actively supported a

national system of standards and testing. In any event, she reasons,

the development of national standards and tests is a project for the

next decade, and should be outside partisan interests or control.

As for NAEP's norms and cut scores, Diane contends that the

assessment's standards are entirely nonpolitical and benchmarked to

international standards. Deborah thinks that Diane's hopes for

unbiased, apolitical benchmarking are well-intentioned but inaccurate

as a description of all the current tests, including NAEP. Having

abandoned the normal curve, she believes, we're stuck with the

fallibility of human judgment.

The establishment of a national curriculum and national testing has

its dangers, Diane concedes, but the consequences of preserving the

status quo may be even more dangerous for the nation's future. On this

point—opposition to preserving the status quo—both Diane and Deborah

agree. The question becomes one of difficult trade-offs and differing

judgments of which dangers are worth risking. Putting these

disagreements out onto the public stage is, we believe, essential to

democratic decisionmaking.

So this is where our conversation left us—at the heart of a conflict

that is not so much over our ideals, our hopes for our own children,

or our dreams for America, but over the trade-offs we are prepared to

risk, in the short run or the long run, to achieve our common vision.

As the lunch ended, Diane said to Deborah, "I would be glad to see my

grandchildren attend a school that you led." Our macro-level

differences do not interfere with our mutual respect for each other's

work. That itself is something we hope our schools can help teach

young people.

Our differences helped us consider ways to rethink our ideas and find

places where those holding different views might compromise, and

perhaps learn to live under one umbrella. What we hope to model is the

idea of democratic engagement, the notion that citizens need to think

about and debate their beliefs and values with others who do not

necessarily share all of them. We want the issues connected to

schooling to be a matter for discussion among all people who care.

We don't have it in our power to solve the problems that confront

American education—not those that take place within the schoolhouse,

much less those that have a direct impact on children's ability to

learn, such as their unequal access to health care, housing, and

myriad other life necessities. But we hope that we have it in our

power to provoke the thinking that must precede, accompany, and follow

any attempt to reform—perhaps, even better, to transform—our schools.

Deborah Meier has spent four decades working in and writing about

public schools. She was the founder of a network of small public

elementary and secondary schools in New York City and Boston,

including the Central Park East schools in East Harlem. She currently

is a senior scholar and adjunct professor at New York University's

Steinhardt School of Education.

Diane Ravitch is an education historian and a former assistant U.S.

secretary of education under President George H.W. Bush. She was

appointed by the Clinton administration to serve two terms on the

National Assessment Governing Board, which supervises the National

Assessment of Educational Progress. Now a research professor of

education at NYU, she is a senior fellow at both the Brookings

Institution, in Washington, and the Hoover Institution, in Stanford,

Calif.

Vol. 25, Issue 38, Pages 36-37, 44

Post a Comment