"We looked at good schools, and they were autonomous, and made the hypothesis that autonomous was an important ingredient," said Tom Vander Ark, the foundation's outgoing executive director of education giving. "But there were problems with that hypothesis ... and I think we know today that what struggling schools need more than autonomy is guidance."

Foundation's small-schools experiment has yet to yield big results

By Linda Shaw Seattle Times staff reporterTyee High School essentially ceased to exist last year.

Its building still stands a few blocks east of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, but three new, smaller schools now share its old space, each with its own principal, its own classes, its own theme. The three still cheer for one, combined football team — sports is the one place the old Tyee remains. But each school will probably have its own graduation this spring.

Tyee, however, is one of the few Washington high schools to come close to what the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation first envisioned when it started giving grants to help big schools carve themselves into smaller units — ideally, with no more than 400 students.

The experiment — an attempt to downsize the American high school — has proven less successful than hoped.

The changes were often so divisive — and the academic results so mixed — that the Gates Foundation has stopped always pushing small as a first step in improving big high schools. Instead, it's now also working directly on instruction, giving grants to improve math and science instruction, for example.

Most of the dozen-and-a-half Washington schools with so-called "conversion" grants have ended up only as hybrids — a mix of small-school elements added to big-school features.

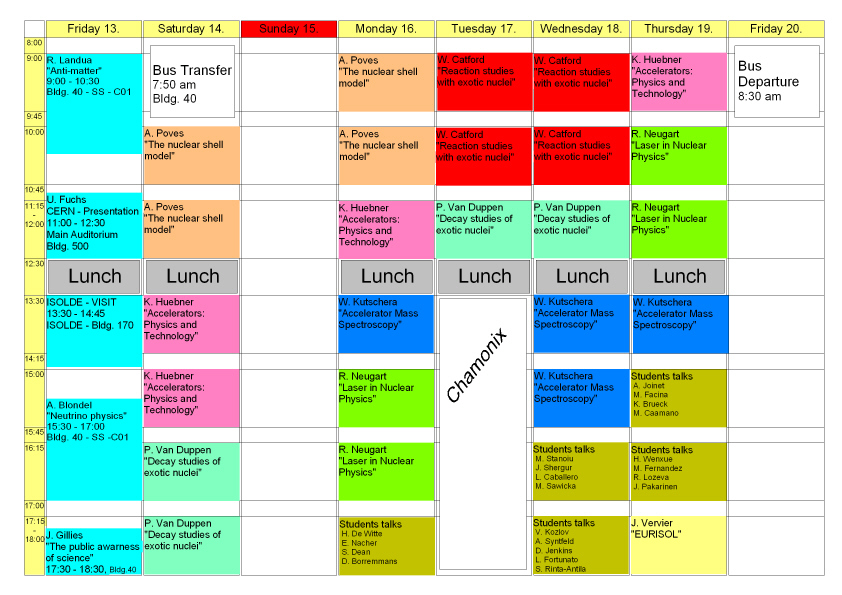

Education givingThe Gates Foundation has given about $1.4 billion in education grants since 1999, most of which are tied to improving high schools. The money has been given to states, districts and individual schools, and has helped start or redesign more than 2,000 new schools across the nation.

In Washington state, the foundation has given about $140 million to school districts and schools, in addition to college scholarships. With the help of foundation grants, nearly 20 Washington high schools are working to break themselves up into smaller units — either as independent small schools or what's called "small learning communities" where students spend the majority of the school day.

What's considered a "small school"? The Gates Foundation defines "small" as roughly 400 students, or about 100 per grade level.

Source: Bill & Melinda Gates FoundationNationally, one high school in Denver abandoned the effort, at least for awhile. In Washington, staff at Henry Foss High in Tacoma and Davis High in Yakima clashed over how — or whether — to do it.

"We looked at good schools, and they were autonomous, and made the hypothesis that autonomous was an important ingredient," said Tom Vander Ark, the foundation's outgoing executive director of education giving. "But there were problems with that hypothesis ... and I think we know today that what struggling schools need more than autonomy is guidance."

The Gates Foundation's push to shrink public high schools has been the best-known hallmark of its education giving. About the time it began in 1999, the foundation said typical comprehensive high schools needed a major overhaul if they were going to reduce the dropout rate and prepare all students for college or work.

The foundation looked around the country for schools that achieved those goals and found that many were small — places where teachers and students knew each other well, and no one could slide by, or even disappear, without notice.

In the past six years, the foundation has given grants to more than 2,000 high schools — of which about 800 were existing schools attempting to create smaller schools within schools.

In theory, the big-school breakups are a way to keep using school buildings that would be too expensive to abandon, and create smaller high schools at the same time. But it was always a gamble.

"It has clearly been an important learning process for us ... and for these districts and schools," Vander Ark said.

Striving to achieveAbout a dozen and a half Washington high schools were some of the first to attempt to convert from big to small.

Most were part of a program, started in 2001, that paired school-improvement grants with generous college scholarships. Called the Achievers program, it was open to schools with large numbers of low-income students. They each received about $500 per student over five years to help them create so-called "small learning communities" — as autonomous as possible.

All of the Washington schools have made a number of changes aimed at making their campuses feel smaller.

At many, for example, freshmen and sophomores spend all or most of their day in a small "school" or "academy," where they know their classmates and teachers better than they could in a larger school.

Teachers usually have opportunities to meet to coordinate lessons and discuss students they share.

Many of the schools also instituted "advisories," in which one teacher meets regularly with a group of students to mentor and advise them.

The schools say such a middle road was the practical approach, and it has yielded improvements, especially in attendance and behavior. But academic-achievement gains have not been dramatic.

The change has also proven much more difficult than the Gates Foundation or school leaders imagined. Parents pushed to keep classes and programs. Districts didn't always support the change. Teachers spent long hours debating how — and whether — to do it.

"We argued more than we collaborated," said Lee Maras, principal at Davis High in Yakima.

At Foss and Davis, for example, the majority of the faculty at one point voted not to seek additional funding from the Gates foundation.

Tyee, Clover Park High in Lakewood, Pierce County, and one of the "small schools" at Enumclaw High are the schools in this state that have done the most to replace their bigger selves with smaller schools that operate independently.

The rest aren't close to being fully independent institutions. That's partly because of logistics and partly due to beliefs that students should be able to choose from a wide range of courses.

Most of the schools, for example, allow "crossovers," where students — especially juniors and seniors — can take classes outside of their small schools.

Small-school advocates say that such "crossovers" dilute the personal climate that's the biggest strength of small schools.

Yet even Tyee and Clover Park allow a few.

At Davis, the staff failed to agree on how or whether to break itself into smaller pieces, Maras said. Some teachers didn't want to break up some of the school's existing programs — such as International Baccalaureate and English as a Second Language.

For a time, Maras said, he felt he'd failed to do what was needed to help Davis improve. But then he said he realized that, through all the debate, staff agreed to improve instruction and find ways to make the campus more personal — and were seeing results.

"We were having all of these difficulties trying to achieve something that might not have been the most important thing," he said.

Worth the effort?

Some small-school advocates question whether a school that's a mix of big and small is worth the effort.

"Some would say they get the worst of both worlds," said Rick Lear, director of the Small Schools Project, which has received Gates grants to help Foss, Mountlake Terrace High and other schools. "I know they don't get the best of small schools out of it."

He noted that teachers, in particular, don't get the benefits of seeing fewer students each day, as they would in a true small school.

Valerie Lee, a University of Michigan professor and co-author of a new book about five big-school conversions, cautions that the phenomenon is still so new it's hard to draw hard conclusions about its value.

One troubling finding, Lee said, was that social stratification at all five schools increased, with the motivated students with good grades gravitating toward one or two of the smaller units, and unmotivated students to others.

"The students and teachers all recognized that there was one subunit where all the loser kids were," Lee said. "We had kids say: 'We know we're losers, and here we are all together in the loser academy.' "

The Gates Foundation, however, says it thinks most of its grantees have made good progress, with more low-income students in challenging classes and on a college track.

"I think it's safe to say it's left them all in a better place," Vander Ark said.

He says he's not bothered by the fact that most of the schools haven't broken themselves into fully independent subunits. He still thinks schools need to be small; he says he hasn't seen a big-school model that's working well. But changing a school's size, he said, isn't always the best starting point.

Going forward, the foundation is advocating a core curriculum that all high-school students would be expected to take, he said. And it wants to help improve math and science instruction by backing efforts to increase math requirements for high-school students, and to train more math and science teachers and pay them better.

He expects those efforts to be just as controversial and difficult as changing the structure of high schools.

Many of the conversion schools' leaders say they're finally spending more time on improving instruction, too, after years of working through all the debates and details of changes in structure.

"To get our heads around it ... took some time," said Mountlake Terrace principal Greg Schwab. "It still is taking some time."

Linda Shaw: 206-464-2359 or

lshaw@seattletimes.comCopyright © 2006 The Seattle Times Company